Why High-Achievers Are Surprisingly Bad at Big Decisions

The scientific method for navigating career pivots, relationships, and life direction

The Crisis That Changed Everything

The conversation happened on a Tuesday morning in Sydney, 9,000 miles from home. Short sentences that demolished two years of blood, sweat, and a single tear slowly tracing its way down my cheek: my PhD funding had been pulled. No explanation, no appeal process, no backup plan. Good luck.

My emotional brain had an immediate, crystal-clear response: Quit. Pack your bags. You've been screwed over and humiliated. Cut your losses and gtfo.

The intensity of my reaction surprised me. I felt peaks of frustration, anger, sadness, and bitterness that were higher than normal. All emotional overreactions that, thanks to years of meditation practice, I recognized as a signal that something was off.

What I came to realize was that these emotions were my ancient, primal wiring trying to grab the wheel, control the radio, and choose the final destination of my entire academic career.

That's too much power to give to the most animal-like parts of my brain.

Instead of letting my emotional brain make a decision that would reshape my entire life, I realized I needed a different approach. I needed to channel the newest part of my brain, (the prefrontal cortex if ya fancy), to think like a scientist.

In that moment of crisis, one question cut through all the emotional noise:

"How would I know what the right decision actually is?"

That question became the foundation for everything that followed.

Three years later, I finished that PhD (finally), launched a consulting career, and now help executives navigate their own complex decisions for the organizations and people they lead. The systematic thinking framework that saved my academic career has since transformed how I approach every major choice from career transitions to where to live to how I evaluate information in our increasingly noisy world.

It is one of the gifts of my PhD, a way of thinking more valuable to me than the letters behind my name.

Which brings me to you.

What if I told you that most of the decisions shaping your life right now are being made by the wrong part of your brain?

Think about your last major decision.

Did you agonize over it for weeks, flip-flop between options, or rush toward what "looked right" because sitting with uncertainty felt unbearable?

You're not alone. The very traits that made you successful in one domain often sabotage you when facing genuinely uncertain choices.

Why Smart People Make Terrible Decisions

Here's the uncomfortable truth about people who've tasted excellence in at least one domain: We're exceptional at execution but surprisingly terrible at decision-making under uncertainty.

We've been trained to have the right answer, to be the person others turn to for solutions, to figure it out quickly and move forward with confidence. This serves us well when we're operating in familiar territory: the sport we've mastered, the academic subject we've studied, the professional domain where we've built expertise.

But when facing genuinely uncertain decisions (career pivots, relationship choices, life direction changes), this same performance, success, and achievement oriented mindset becomes a liability.

Instead of asking "How would I know if this is right for me?" we rush toward what looks impressive based on external markers of success rather than what actually serves our authentic path.

We make decisions to maintain our image as someone who "has it figured out" rather than admitting we're navigating uncharted territory.

We let inherited stories and unconscious biases drive our choices because slowing down to examine them feels like weakness.

The identity component here is crucial. For someone whose self-worth has been built on competence and having answers, saying "I don't know" feels like admitting failure. The terror of appearing incompetent often drives us to make quick decisions based on incomplete information rather than designing systematic ways to gather better data.

This is how smart, capable people end up in careers that look impressive but feel hollow, relationships that check the right boxes but lack genuine connection, or life paths that satisfy everyone else's definition of success while leaving us feeling empty.

The Scientific Method for Life Decisions: Mini-Experiments and "How Would I Know?"

There's a better way to navigate uncertainty, one that starts with a simple but powerful question: How would I know?

This matters more than you might think.

We live in a world where everyone has infinite options and nothing feels permanent. Most people respond to this by either getting stuck in endless research mode or making quick decisions they later regret. Meanwhile, you'll be the person who actually knows what they're talking about because you've tested your assumptions. You'll be making moves that serve your authentic path instead of just looking good on paper.

This approach is grounded in what philosophers call critical realism: the understanding that while reality exists independently of our perceptions, we can only know it imperfectly through systematic inquiry.

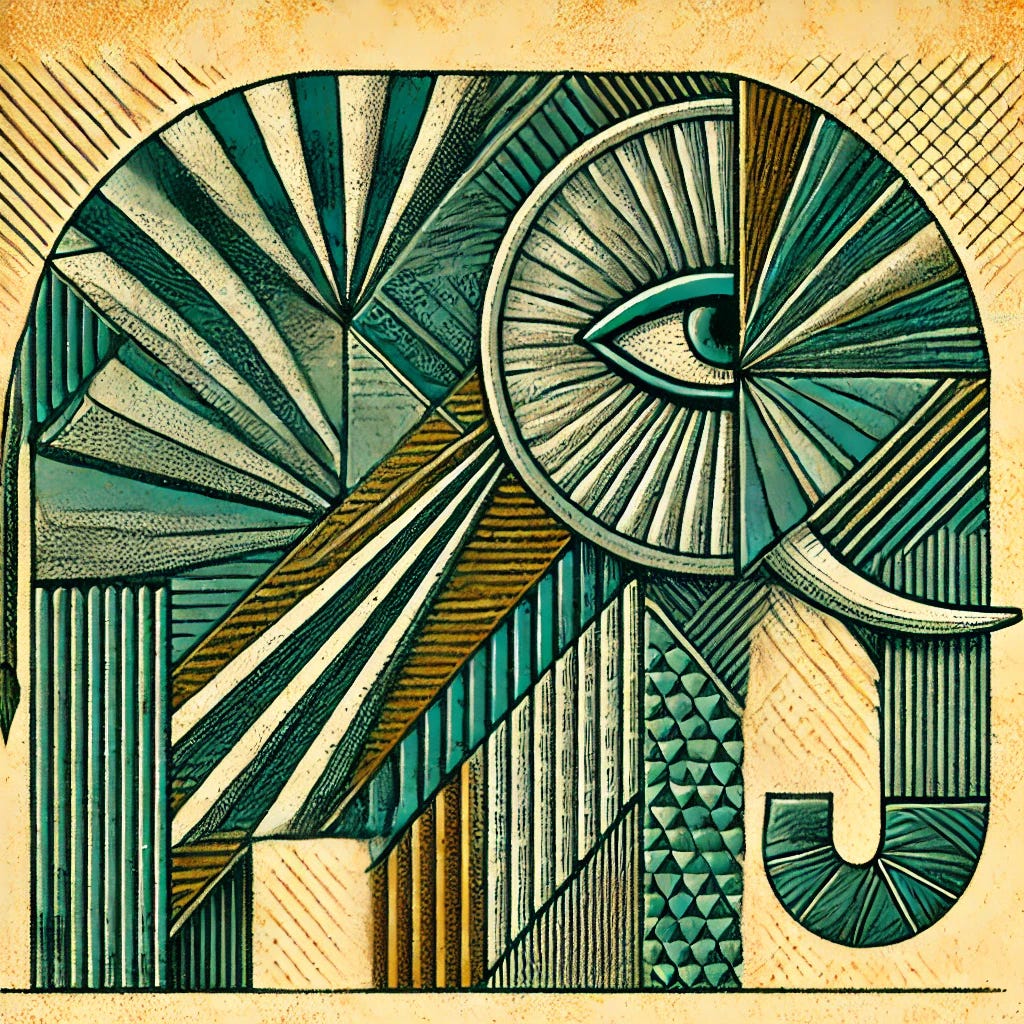

There's an old parable from India about blind people trying to understand an elephant. One person touches the trunk and says "An elephant is like a snake." Another feels the leg and says "No, it's like a tree trunk." A third touches the ear and insists "You're both wrong. It is like a fan."

Who's right?

Everyone is.

And no one is completely right.

Here's what this teaches us about life decisions: When you're trying to decide something important like what career to pursue, there ARE real answers about what would contribute to your happiness and fulfillment. There's likely a whole category of jobs that would fit you well, and many more that won't. But you can't see the complete picture from where you're standing right now. You only have partial information. The elephant exists, it's real, but your current experience isn't the whole truth.

So instead of pretending you know the complete truth ("I KNOW this specific job will make me happy") or throwing your hands up to the gods of nihilism because perfect certainty is impossible ("I can't know anything for sure so fck it"), you ask: How would I know?

You try different experiments.

You look from different angles.

You test small pieces of your assumptions.

Each experiment gets you a little closer to understanding what actually works for you. You'll never have perfect information, but you can have much better information.

In practical terms, this means approaching major life decisions the same way a scientist approaches research questions: with curiosity rather than certainty, experiments rather than assumptions, and evidence alongside emotion as the primary guides.

The scientific method, one of the greatest inventions of humanity, is a framework for cutting through our own biases and stories to make decisions aligned with reality rather than wishful thinking. And you don't need an advanced degree, a laboratory, or 7 years of a doctorate overseas to use it in your own life.

Here's how it works in practice:

Observation: Notice what's actually happening, not what you think should be happening or what others expect to be happening.

Question: Formulate specific, testable questions rather than vague anxieties or assumptions.

Hypothesis: Make educated predictions based on available evidence, not just gut instinct or social pressure.

Mini-Experiments: Design small, low-risk tests to gather data rather than betting everything on one big decision.

Analysis: Examine results objectively, including data that contradicts your preferences.

Iteration: Use what you learn to refine your understanding and design a better life.

The key insight is in the "mini-experiments": small, designed tests that help you gather real-world data about your assumptions.

Instead of agonizing over whether a career change is right for you, you design ways to test it through informational interviews, volunteer projects, part-time work, or shadowing someone in the field, all to give you insight and better answers to the question “How would I know?”

Worried about whether you'd enjoy living in a different city? How would you know? Maybe you spend a month there, talk to locals, explore different neighborhoods, experience the daily rhythms rather than just visiting as a tourist.

Uncertain whether a relationship has long-term potential? Well, how would you know? Perhaps you travel together, see how you handle conflict, spend time with each other's families, observe how they treat service workers when they're stressed.

The beauty of this approach is that you can learn something valuable regardless of the outcome. Even "failed" experiments provide crucial data about what doesn't work for you.

Real-World Tests: When Experiments Surprise You

Let me share how this plays out in practice, showing how this approach transforms messy uncertainty into manageable experiments.

The LinkedIn Experiment

After six months of writing once weekly on LinkedIn (which I loved), I decided to scale up to five times a week for six months. My question became: How would I know if more frequent posting would actually serve my goals? My hypothesis was that more frequent posting would accelerate audience growth and business opportunities. Part of the pressure came from ideas about branding and reach that I'd absorbed from the platform.

I upheld the commitment for the full six months, but the analysis revealed something unexpected: the increased frequency was pushing me to write too superficially, crafting posts for "the market" rather than expressing authentic insights. I was optimizing for engagement rather than truth. And it burned me out.

The experiment taught me that more isn't always better. It led me to Substack (we’re here right now!) where I could write longer, more thoughtful pieces less frequently, which felt far more aligned with my authentic voice.

The Jiu Jitsu Investigation

After a back injury ended my soccer playing days, I needed a new physical practice. Ironically, despite being a martial art where people actively try to choke you and break your limbs, jiu jitsu seemed like a potentially safer pursuit than the sport that had led to my injury. My hypothesis was that Brazilian Jiu Jitsu would provide the competitive outlet and community I was missing. I joined the first gym I found and struggled for months, feeling lost, overwhelmed, and convinced I was terrible at it.

The question became: How would I know if jiu jitsu wasn't for me, or if this particular environment wasn't serving my learning style?

I tried a different gym with smaller classes, more personal attention, and instructors who learned my name. Same sport, completely different experience. The mini-experiment of switching gyms revealed that my initial struggle was about environment and instruction quality, not my aptitude for the sport.

The PhD Strategy

Back to that funding crisis. Once I recognized my emotional overreaction as a signal rather than a directive, I approached the decision systematically. My question was: How would I know what my actual options were for completing this degree or transitioning to something else?

I researched other universities I could transfer to, investigated alternative funding sources, and had conversations with people who had completed their PhD programs to understand their career trajectories. My hypothesis was that with strategic planning, I could find a way to complete the degree that aligned with my financial and personal constraints.

The experiments included applying to transfer programs, taking on multiple part-time jobs to fund my studies, and networking with professionals in fields I might want to enter.

The analysis revealed that while finishing the PhD would require significant sacrifice, it was achievable and provided both valuable skills and kept more doors open for my next career phase.

None of these experiments went exactly as planned, but each provided crucial data that informed better decisions and ultimately improved my life.

From "Having Answers" to "Finding Answers"

Making this transition from emotional to systematic decision-making requires a fundamental identity shift, especially for those accustomed to having the right answer.

You have to move from "I should know the answer" to "I can design a way to find out."

This isn't just a cognitive change but an emotional one that challenges core beliefs about competence and worth.

Here are four mindset shifts to be aware of:

Permission to Not Know: Excellence in systematic thinking means embracing uncertainty as the starting point, not something to be quickly eliminated.

The phrase "I don't know, but here's how I could find out" becomes a statement of competence, not inadequacy.Comfort with "Failed" Experiments: When a test doesn't deliver the results you hoped for, that's not failure but successful data collection.

The goal isn't to be right about your initial hypothesis; it's to learn something useful regardless of the outcome.Patience Over Action Bias: High-achievers are wired to solve problems by working harder and moving faster. Systematic thinking sometimes requires slowing down, gathering more data, and testing smaller hypotheses first.

This can feel like procrastination but it's actually a more sophisticated form of problem-solving.Good Evidence Over Perfect Information: The goal isn't to eliminate all uncertainty before acting but to gather enough good evidence to make reasonably informed decisions.

Critical realism reminds us that we'll never have perfect information about complex life choices.

And that's okay.

The question "How would I know?" isn't meant to paralyze you with endless research but to give you confidence that you've done your due diligence. Sometimes a bad outcome reflects circumstances beyond your control, not a flawed decision-making process.

The standard is "good enough evidence to act wisely," not "perfect prediction of outcomes."

The identity shift is from seeing yourself as someone who should have it all figured out to someone who excels at figuring things out. That's a crucial distinction that transforms how you approach uncertainty from a source of anxiety into an opportunity for discovery.

Your Decision-Making Toolkit

The most powerful question in this entire framework remains: "How would I know?" Here's how to apply it systematically to your own decisions, whether you're navigating career transitions, relationship choices, or life direction changes.

Observation Stage Questions

What's actually happening in my situation right now (versus what I think should be happening)?

Where am I feeling emotional intensity that might signal important data?

What patterns do I notice in my reactions or behaviors?

Question Formulation

What specifically am I trying to decide or understand?

What's the real question beneath my surface concern?

How can I make this question specific and testable?

Hypothesis Development

Based on available evidence, what do I predict will happen?

What assumptions am I making that I could test?

What would I expect to see if this assumption is correct?

Mini-Experiment Design

What's the smallest, lowest-risk test I could design?

How would I know if my hypothesis is accurate?

What could I learn even if the experiment doesn't go as planned?

Analysis and Iteration

What did the results actually show (versus what I hoped they'd show)?

How does this change my understanding of the situation?

What's my next action based on what I learned?

These questions work as coaching prompts for yourself or others. The goal isn't to eliminate intuition or emotion from decision-making but to ensure they're informed by evidence rather than driven by unconscious biases or inherited stories.

This Week: Pick one decision you're facing and ask "How would I know?"

Design one small experiment you could run in the next 7 days to gather real data about your options and what you could do next.

Let me know what you’re taking on in the comments.

Making It Stick: Rationality as Your Superpower

Here's what's at stake: every major decision in your life will be made either by your highest self or your most primitive wiring.

When you don't consciously choose a decision-making framework, your choices default to whatever emotional pattern or inherited story happens to be loudest in the moment. It's the past, or the noise of the crowd, or limiting beliefs screaming over what you, real you, actually wants.

Again, this is how intelligent, capable people end up living lives that serve someone else's definition of success while leaving them feeling empty and unfulfilled. WE DON’T WANT THAT!

The alternative is rationality. Not rationality as cold, emotionless calculation, but as systematic thinking that integrates both logic and intuition in service of decisions aligned with who you actually are and what you genuinely value. It’s how you get to know which part of the elephant you’re actually dealing with.

Rationality is the human superpower. It's what allows you to step outside your immediate emotional reactions, examine the stories you've inherited about what's possible, and design experiments to test whether those stories serve your authentic path forward.

When you master this approach:

Your decisions become expressions of your values rather than reactions to circumstances.

You spend less time second-guessing yourself because you've systematically gathered relevant data.

You recover faster from setbacks because you've approached choices as experiments rather than permanent commitments.

You build genuine confidence rooted in your ability to navigate uncertainty rather than the illusion of having everything figured out.

Most importantly, you stop being at the mercy of whatever emotional pattern or social pressure happens to be strongest in the moment.

You become the author of your own life rather than a character in someone else's story.

The path forward requires courage. This requires the courage to admit you don't know, to question inherited assumptions, and to design experiments that might not deliver the results you're hoping for.

But it's also the path to a life that's genuinely yours rather than a performance for an audience you may not even respect.

Most people will keep making decisions with their emotional brain because it feels easier in the moment. But you're not most people. You're someone who chooses the harder path because it leads somewhere worth going.

The framework is simple:

Notice what's actually happening.

Ask "How would I know?"

Design a small test.

Act on the data.

Rinse and repeat.

Your next major decision is coming whether you're ready or not. The question is: who's going to make it? Your emotional brain operating on outdated programming, or your highest self armed with systematic thinking and evidence-based choice-making?

I'm Danny Kenny, and I've spent over a decade exploring the intersection of behavioral science, decision-making, and authentic achievement. If this framework resonates with you, subscribe below to receive new articles on living deliberately in a world designed to keep you reactive.